Text and photographs by Nicole Bouglouan

From a personal observation in Monfragüe Park – Extremadura - Spain

Sources:

Birdlife International – Data Zone

Programa de conservación del Águila Imperial ibérica - Alzando el vuelo - SEO BirdLife

E Ciencia – Especies españolas en peligro de extinción

Ornithomedia - Le Web de l’Ornithologie

HANDBOOK OF THE BIRDS OF THE WORLD Vol 2 by Josep del Hoyo-Andrew Elliot-Jordi Sargatal - Lynx Edicions - ISBN: 8487334156

GUIDE DES RAPACES DIURNES – Europe, Afrique du Nord et Moyen-Orient de Benny Génsbol – Delachaux et Niestlé – ISBN : 2603013270

Card Spanish Imperial Eagle

Page Birds of prey

THE SPANISH IMPERIAL EAGLE

SPANISH MOUNTAIN’S SYMBOL

The Spanish Imperial Eagle has been discovered in 1860 by the German naturalist Dr. Reinaldo Brehm (Renthendorf, 1830 – Barcelona, 1891).

The first research about the Spanish Imperial Eagle was financed by the Prince Albert of Bavaria, great friend of the naturalist. That explains why Dr. Reinaldo Brehm gave the name of Prince’s Albert Eagle (Aquila adalberti) as a tribute to his friend.

This large eagle is a gift for all the bird lovers watching for his silhouette soaring over the rocky cliffs of Spanish mountains. The Spanish Imperial Eagle appears as a survivor after numerous years of persecutions, poisoning, habitat destruction, power lines and reduction of numbers of his preferred preys, rabbits.

Today, thanks to several conservation and protection programs, this species is slowly recovering better numbers. But it is still considered as Vulnerable, with low but increasing numbers. The last counts gave 536 pairs in Spain in 2017, but in 2021, there were 821 pairs present in Spain.

The Spanish Imperial Eagle could be very similar to the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysateos), but the white shoulder’s feathers allow a good identification. He is living only in Spain and Portugal, but formerly, his range probably included North Africa and Southern France.

This species is sedentary, but the young birds may wander over some distance, sometimes to the former range.

This large eagle hunts for food, and his preferred prey is the rabbit, but partridges and other birds, mammals, some reptiles, fish and carrion are also taken according to the prey availability.

He frequents plains and hills with cork-oaks or pines, and can be seen near streams and marshes. He may nest in mountains, from 300-900 metres up to 1500 metres of elevation.

As soon as January, the mates perform typical aerial displays, flying together and turning with legs and talons held towards each other, tumbling and rising again into the air. This is very spectacular!

The stick nest placed at tree top is often reused year after year, but they may change and have several nests. This species breeds around 1000 metres of elevation, sometimes lower or higher according to the location.

The laying occurs between mid-February and late March. The female, and sometimes the male, incubate the two-three eggs during about 40-43 days. The white downy chicks are aggressive as soon as they hatch. The smallest may die but all the chicks may grow successfully too. The young birds fledge about two months later, and have a beautiful pale brown plumage with white streaks and spots. They get the adult appearance at 5-6 years old. The family members often spend the winter together.

Usually, the raptor appears coming from nowhere, his large shadow contrasting against the pale sky. But then, little by little, he flies into the light. The dark plumage and the white shoulders make him unmistakable.

He soars quietly on thermals above his territory, watching for intruders, while the female incubates the eggs in the large stick nest at top of some cork-oak near the cliff, completely hidden among the dense vegetation.

Sometimes, he joins her and both perch on the rim. At this moment, the white feathers allow us to see them partially and briefly. He takes off again and the female continues her task, in order to carry the incubation through to a successful conclusion because these eggs are precious. The male regularly feeds her, and may sit on the nest for a short moment while the female flies away. But she returns soon and the male goes away for hunting.

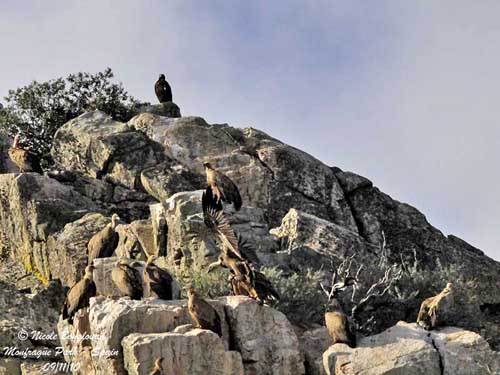

His preferred perch is the cliff top, among the vultures, often above them because the Spanish Imperial Eagle does not like them. Sometimes they may rest together, relatively close to each other on the rocks. But today, the eagle is upset and some aggressive chases can be observed.

The Spanish Imperial Eagle is soaring among several Eurasian Griffon Vultures (Gyps fulvus), when suddenly, he dives onto the one below. He pursues the large raptor during one or two minutes, and performs some threat displays. He holds his legs towards the vulture with outstretched talons. And finally, the eagle turns and reaches the cliff top, as usual.

But one vulture joins him and perches close to the eagle. One minute later, a second vulture arrives, but the eagle is still upset and performs again threat displays and calls. Then, he takes off and flies away, leaving the two perched vultures.

I do not know very well why the eagle threatens the vultures. But an observation by SEO BirdLife - Spain, may give an explanation. Thanks to a video, we can see a vulture coming to an abandoned eagle’s nest, maybe searching for chicks of eggs, or nest materials? But later, a second vulture joins the first and the one in the nest is moving a stick with the bill. Is it a pair?

We know that Eurasian Griffon Vultures nest in cliff faces on rocky ledges, and maybe they need some sticks more to arrange the nest? I do not have the answer.

A second video shows the eagle returning to his nest, but he also takes a long branch with leaves from the rim and flies away. This behaviour probably indicates a change of nest. The eagle prefers to build a new nest in order to protect his young against the vultures.

These facts could explain the threat behaviour recently observed.

Another interesting observation show the large eagle harassed by the two Iberian Magpies (Cyanopica cooki). These birds also nest in cork-oaks, and the presence of the raptor close to their nest is a threat for the young magpies. So, they fly around him, very close, and dive bomb onto the eagle which remains quietly perched on his rock. But after several attacks, he takes off, pursued by the angry corvids!

We saw the Spanish Imperial Eagle several times in Extremadura, as well in the steppes searching for rabbits, as more often in Monfragüe Park. The cliffs are isolated and protected from the road by the meanders of the Tagus River. Numerous Eurasian Griffon Vultures inhabit these rocky faces where their white downy chicks hatch every year.

The eagle nests in cork-oak or pine in the surroundings of the cliffs. Sometimes, he perches on dead branch in tree, in the vicinity of the nest. His dark plumage contrasts against the green vegetation. But from the observatory, our eyes only see a small dark spot! He is really the king of the park and we enjoy his presence when he deigns to appear above his domain.

Through a recent observation, we saw again an altercation in the sky between the Spanish Imperial Eagle and the Eurasian Griffon Vulture.

The eagle is perched on its usual dead branch in the vicinity of the nest-site used the last season. The raptor is within its territory. But this area is also occupied by a large colony of vultures. They must share the territory, and usually, they are able to live close to each other. Their hunting behaviour is not the same. No competition for food!

But they have to share the sky… Numerous vultures are soaring around the cliffs where they breed and are living all year round. We can see them flying in tandem, with several other vultures flying around the pairs.

The eagle is flying too in the same area, circling quietly in thermals. Sometimes, one or two vultures are passing by…

And suddenly, vulture and eagle are facing each other. The large vulture almost stands up with the wings widely open, while the eagle is flying on its back with legs and talons hold forwards in front of the vulture.

During less than one second, both raptors are facing each other with the wings widely spread while flying.

The time for them to regain their balance, they continue their way until the next encounter in the sky.

The vulture returns to the cliff and the eagle to its perch… See you soon!!!

This type of behaviour occurs regularly and lasts a few seconds. This is not a direct attack, but probably an intimidation attempt in order to remind the vulture to keep its distance from the eagle’s nest.

Territorial eagles may harass Eurasian Griffon Vultures if they are flying in the vicinity of their nest-sites, involving this type of aggressive behaviour. Sometimes, this kind of competition may lead to aggressive interference or mutual avoidance. Both are regularly observed and the show is always worth seeing!

But sometimes, it leaves its branch and starts to collect nest materials. It reaches the left side of the cliff and alights in a cork-oak. It undertakes to cut small branches with its beak, and this work is not easy to do! Finally, after about two minutes, the eagle takes off from the tree with a small branch in the bill, and returns to the nest hidden in the dense foliage of a cork-oak.

In February, the copulation occurs, and usually takes place on their favourite dead branch. The female is perched and very quiet, but suddenly, she moves and crouches with semi-open wings and lowered head and neck. At this moment, the male emerges from the foliage and perches on the branch where the female waits for him. Slowly, it approaches her while calling softly.

Then, step by step, it joins her and mounts the female, and the copulation occurs. We can see the conspicuous white wing pattern of both eagles while they are working for the future of their rare species.

Once mating is finished, male and female separate and remain perched together on their branch, looking over their territory. Nest building will be achieved very soon and the female will lay her eggs. We hope that all the brood will survive and grow up in this so beautiful place.