Text by Nicole Bouglouan

Photographers:

Patrick Ingremeau

TAMANDUA

Rod Morris

Courtesy of Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai, 1975

Department of Conservation

Illustrators :

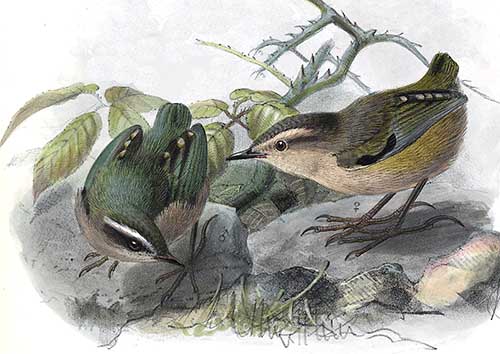

William Lawry Buller (1838-1906)

John Gerrard Keulemans (1842-1912)

Sources:

HANDBOOK OF THE BIRDS OF THE WORLD Vol 9 - by Josep del Hoyo - Andrew Elliot - David Christie - Lynx Edicions - ISBN: 8487334695

KNOW YOUR NEW ZEALAND BIRDS by Lynnette Moon - New Holland Publishers – ISBN: 1869660897

New Zealand birds and birding (Narena Olliver)

Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia

CREAGUS@Monterey Bay (Don Roberson)

BirdLife International (BirdLife International)

ACANTHISITTIDAE FAMILY

New Zealand wrens

Rifleman, New Zealand Rockwren, Bush Wren, Stephens Island Wren

New Zealand endemic species

These tiny passerines are regarded as one of the oldest living groups of the New Zealand endemic bird species, and they may be older even than the Kiwis (Apterygidae family).

In spite of numerous studies of fossil bones found in some cave sites and in deposits accumulated by avian predators, the true relationships of this family have remained unclear for long time. The New Zealand wrens are surviving species of an ancient lineage of passerines with no close living relatives. They are not at all closely related to the true wrens (Family Troglodytidae).

The family Acanthisittidae includes at least seven species, formerly with five genera, but today, only four are accepted, Acanthisitta, Xenicus, Pachyplichas and Dendroscansor.

There are two surviving species, the Rifleman (Acanthisitta chloris), locally common or widespread according to the range, and the New Zealand Rockwren (Xenicus gilviventris) listed as Vulnerable. Both are still present in New Zealand but they are patchily distributed throughout the country.

Juvenile race "granti"

The Bush Wren (Xenicus longipes) is probably extinct. Among some others, only the two last authenticated reports attest to its presence in 1966 and 1968. It has never been seen since this period.

The Stephens Island Wren (Xenicus lyalli) is extinct since 1894. It died very soon after its discovery.

But three other species have been described from fossil bones. These species probably died out following the Maori settlement of New Zealand, around the year 1250.

Two species have been described in 1988, and belong to the genus Pachyplichas. These wrens, the North Island Stout-legged Wren (Pachyplichas jagmi) and the South Island Stout-legged Wren (Pachyplichas yaldwyni) were flightless.

The latest species, the Long-billed Wren (Dendroscansor decuvirostris) was flightless too, and was the only New Zealand wren having a conspicuous curved bill.

Each species shows some peculiar morphological features, adapted to behaviour and habitat. Their common feature is the pale buff to creamy-white supercilium conspicuous in all species. Upperparts are darker than underparts.

The Rifleman (6-7g) has slightly upcurved bill used for probing into moss and bark while searching for insects. It has long legs, toes and claws, and especially the hind toe. This is for better grip when the bird clings along the tree trunks or hangs upside down when gleaning in crevices.

This species frequents forests and scrub, and is usually found in the larger remaining tracts of forest. The race “chloris” occurs on South Island and Codfish Island, whereas the race “granti” is found on North Island.

Juvenile race "granti"

The New Zealand Rockwren (16-20g) has long legs set back on the body, long toes and claws. These features allow the bird to scramble, hops and perch on rocks and boulders.

It occurs in alpine and subalpine areas on South Island.

The Bush Wren (16g) had longer legs and toes than the Rifleman, for foraging more among branches than on tree trunks. The race “variabilis” from Stewart Island was foraging among low vegetation, spending much time on the ground, and even entering petrel’s burrows. This species was found in mountainous areas in forest and scrub in North and South Islands, Kapiti Island, Stewart Island and the three nearby South Cape islands.

The Stephens Island Wren was flightless, with small, rounded wings and reduced wing skeleton. It had robust bill and legs, and big feet. This semi-nocturnal bird was similar to a mouse while running quickly on the ground. Living birds were seen within dense forest in rocky areas. This species was widespread in North and South Islands. There was a population on Stephen’s Island in Cook Strait.

The Long-billed Wren (30g) had a long, downcurved bill, large head, short, thin legs and some skeletal features suggesting that it moved up and down trunks and branches like the Australasian treecreepers, while probing in bark crevices for food. It was flightless too. It was supposed to be arboreal. It was absent from the lowland forests, but mainly found in subalpine vegetation. Some fossils were found on South Island, in NW Nelson and Southland.

The two Stout-legged Wrens had reduced wings and these birds were flightless. But they had long, robust legs and feet with flat end toe bones and poorly curved claws, suggesting that they were terrestrial species. (Perching birds have curved end toe bones). The South Island Stout-legged Wren (50g) was the largest of the seven species whereas the North Island Stout-legged Wren (45g) was distinctly smaller than the previous. Both had short, stout bill and less depressed cranium.

They were probably more often stood erect on flat ground or stumps, than perched in trees.

The North Island species was found in mixed podocarp and broadleaf lowland forests throughout the North Island.

The South Island species was found throughout the South Island in various forested habitats from lowlands to subalpine areas.

All were probably mainly insect-eaters, but taking occasionally and seasonally seeds, berries and fruits. They forage alone or in pairs, or in family groups.

As weak fliers or flightless birds, the New Zealand wrens are sedentary. Even the New Zealand Rockwren which lives in alpine and subalpine areas does not move in winter.

These physical adaptations to behaviour and habitat may be reminiscent of those of other island’s Passerines, the Darwin’s Finches. Like the Acanthisittidae, these finches have very peculiar morphological features, and especially their beaks, allowing them to survive in their specific environment.

The New Zealand wrens often have permanent pair-bonds. They are regarded as territorial birds because they usually remain in their home range all the year, but they rarely sing or perform territorial displays or fights.

Except for the Rifleman and the New Zealand Rockwren, there is not detailed information about the breeding behaviour of the other species. But we can suggest that it was fairly similar.

Considering that these birds are weak fliers or were flightless, they remain near or on the ground when nesting. The nest is made in natural cavities, often holes in tree trunk or branches, but also among roots, in rock crevices or holes in the ground. The nest is often spherical and built in the cavity. It is made with grass, twigs, moss and rootlets. The inner part is lined with feathers.

After about three weeks of incubation, the chicks hatch and the pair feeds them with insects. They fledge between 23-25 days after hatching, but they remain dependent on adults for food during some weeks more. After the breeding season, the juveniles may disperse short distances.

The Rifleman is known for having helpers which feed and defend the chicks, and remove the faecal sacs. Any information can indicate that other species also had helpers.

Except the Rifleman which is locally common or widespread according to the region, and the New Zealand Rockwren listed as Vulnerable, all the other species are extinct.

The main cause, as well for extant birds as extinct species, is the introduction of mammalian predators such as mice, rats, cats and stoats which take eggs and chicks at nest, and even kill the incubating adult.

Juvenile race "granti"

The Stephen’s Wren and the Bush Wren died out due to massive deforestation and drainage of wetlands following the European settlement.

The three other ancient extinct species died out probably for the same reasons, but following the Maori settlement.

The extant species have restricted range and small populations, and depend now on predator control and protection of the habitat.