Texte de Nicole Bouglouan

PhotographeRs :

John Anderson

John Anderson Photo Galleries

Aurélien Audevard

OUESSANT DIGISCOPING

Steve Garvie

RAINBIRDER Photo galleries & Flickr Rainbirder

Tom Grey

Tom Grey's Bird Pictures & Tom Grey's Bird Pictures 2

Tom Merigan

Tom Merigan’s Photo Galleries

Otto Plantema

Trips around the world

William Price

PBase-tereksandpiper & Flickr William Price

Alan & Ann Tate

AA Bird Photography

Illustrations:

John Gerrard Keulemans (1842-1912)

Great Auk (extinct) in summer and winter plumage

John Gould (1804-1881)

Great auk eating a fish, by John Gould

John Gould: The Birds of Europe, vol. 5 pl. 55 lithograph by Edward Lear with hand coloring. 30.2 x 44 cm (image); 38.3 x 55.5 cm (sheet) Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts

Nicole Bouglouan

PHOTOGRAPHIC RAMBLE

Sources :

HANDBOOK OF THE BIRDS OF THE WORLD Vol 3 by Josep del Hoyo-Andrew Elliott-Jordi Sargatal - Lynx Edicions - ISBN : 8487334202

THE HANDBOOK OF BIRD IDENTIFICATION FOR EUROPE AND THE WESTERN PALEARCTIC by Mark Beaman, Steve Madge - C. Helm - ISBN: 0713639601

OISEAUX DE MER – Guide d’identification de Peter Harrison – Editions Broquet (Canada) – ISBN-10 : 2890004090 – ISBN-13 : 978-2890004092

BirdLife International (BirdLife International)

CREAGUS@Monterey Bay (Don Roberson)

Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia

All About Birds (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

What Bird-The ultimate Bird Guide (Mitchell Waite)

Comparative Reproductive Ecology of the Auks (Family Alcidae) with Emphasis on the Marbled Murrelet

FAMILY ALCIDAE

Auks, auklets, guillemots, murrelets, murres, puffins and Razorbill

The family Alcidae is a very old family with roots extending back 30-40 million years earlier of more. From geological studies, the northern Pacific Ocean was the centre of origin for most or all of the modern Alcids, but more fossils have been recorded in the Atlantic Ocean. However, the presence of Alcids in the Atlantic is much more recent than in Pacific where an evolutionary origin was followed by a spread to the North Atlantic through the Arctic Ocean.

In the past, the Alcidae have been linked to some other families such as Spheniscidae, Gaviidae, Podicipedidae and Pelecanoididae. They are today placed in the order Charadriiformes, but their relationships to groups of this order is still uncertain.

Currently, the family Alcidae comprises 25 species (with one extinct), that separate into eight distinct groups.

The first group is that of a single small species, the Little Auk or Dovekie (Alle alle). It is typically black above and white below with short bill. It is largely restricted to the Atlantic Ocean.

The second group contains three large species, the Common Murre (Uria aalge), the Thick-billed Murre (Uria lomvia) and the Razorbill (Alca torda). They are long-billed, with blackish upperparts and white underparts. The Razorbill is restricted to the Atlantic, whereas the murres can be found in both Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

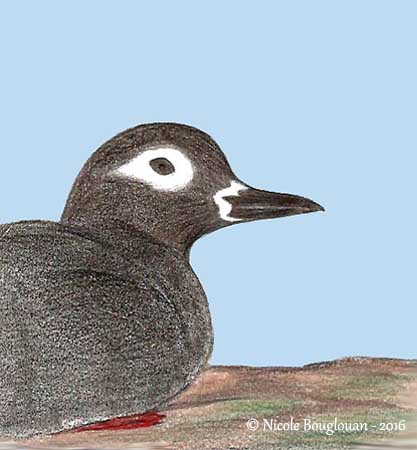

The third group comprises three medium-sized Alcids, the Black Guillemot (Cepphus grille), the Pigeon Guillemot (Cepphus Columba) and the Spectacled Guillemot (Cepphus carbo). They are often all black in summer. The first one is found in the Atlantic, while the two others are in the Pacific.

The fourth group includes three small species, the Marbled Murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus), the Kittlitz’s Murrelet (Brachyramphus brevirostris) and the Long-billed Murrelet (Brachyramphus perdix). They are mostly dark brown in summer with scaled or barred pattern. Both species are found in the Pacific Ocean.

The fifth group comprises four small Alcids, the Guadalupe Murrelet (Synthliboramphus hypoleucus), the Craveri’s Murrelet (Synthliboramphus craveri), the Scripps’s Murrelet (Synthliboramphus scrippsi), the Ancient Murrelet (Synthliboramphus antiquus) and the Japanese Murrelet (Synthliboramphus wumizusume). All are dark above and white below with short bill. They occur in the Pacific Ocean. However, Guadalupe and Craveri’s Murrelets breed and winter along the W coast of N America, from Baja California to S California. The Scripps’s Murrelet reaches British Columbia.

The sixth group is that of five small species such as the Cassin’s Auklet (Ptychoramphus aleuticus), the Parakeet Auklet (Aethia psittacula), the Crested Auklet (Aethia cristatella), the Whiskered Auklet (Aethia pygmaea) and the Least Auklet (Aethia pusilla). They have dark grey upperparts and white to grey underparts, with sometimes scaled or barred pattern. They are short-billed and have some ornamental feathers on the head during the breeding season.

The seventh group is that of another single species, the medium-sized Rhinoceros Auklet (Cerorhinca monocerata). This one has greyish-black upperparts and grey-barred white underparts. The robust bill gives the species its name, and we can see some ornamental feathers on the head in breeding plumage. It is found in the Pacific Ocean.

The eighth group comprises three medium-sized species, the Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica), the Horned Puffin (Fratercula corniculata) and the Tufted Puffin (Fratercula cirrhata). All have black upperparts and white cheeks. The underparts are white, except in Tufted Puffin which has black underparts. They have large, laterally compressed triangular bills, always brightly coloured during the breeding season. The first species occurs mainly in the Atlantic Ocean, whereas the two others can be found in the Pacific Ocean.

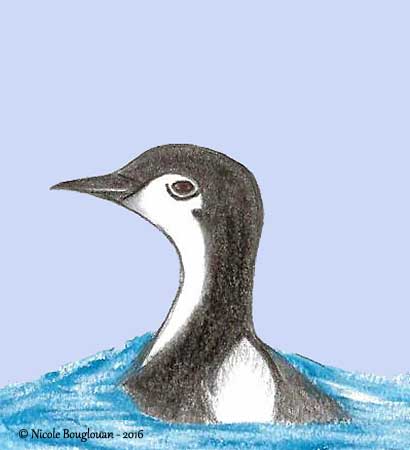

And finally, the extinct Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) was black above and white below, with conspicuous white area in front of the eye in breeding plumage. This species was flightless. It was living in boreal latitudes through the North Atlantic. Its closest living relative is the Razorbill, and the Great Auk is sometimes included within the genus Alca.

John Gerrard Keulemans (1842-1912)

Great Auk (extinct) in summer (left) and winter plumage (right)

Actually, the Alcids could be the penguins of the Northern Hemisphere, even being completely unrelated. Unlike the Spheniscidae, all the living Alcids are able to perform a fast whirring flight. They are good divers and swimmers and pursue their prey underwater, propelled by their short, powerful wings, the short legs and the webbed feet. However, the legs are placed far back on body, and they are usually clumsy on land while walking with an upright posture.

The auks use land only for breeding, and most species breed along the coasts, on headlands and offshore islands. They spend most of the year at sea, in the colder waters of the Northern Hemisphere. They have a circumpolar distribution and can be seen from E Canada through the North Atlantic and eastern shores of the Arctic Ocean, to the Bering Sea and North Pacific.

They winter southwards, but several species remain within or close to their breeding range during winter, and move only according to the food resources. They live continuously at sea where they feed and rest. They often winter in continental shelf waters.

These birds are able to fly in both air and water. They can dive at great depths to pursue a prey, propelled by their short, narrow wings and the webbed feet. However, these morphological features do not help the birds in flight. The take-off is difficult but the flight is fast and direct, with rapid wingbeats. On land, they usually have an upright posture and may appear clumsy.

The auks feed on numerous aquatic prey, from plankton (copepods, euphausiids and amphipods) to fish (larval fish and adults), and forage from near-shore to offshore in deep waters. They can dive at variable depth, with species feeding in the middle upper waters to the sea floor. They are able to dive at great depths, as deep as 100 metres like Uria murres, 40 metres for Cepphus guillemots, and 30 metres for the auklets.

They find all their food in the oceans, by diving from the surface and swimming underwater, propelled by their wings while pursuing a prey. The prey is often swallowed while swimming, and sometimes at the sea bottom like the Cepphus guillemots.

All the Alcids are solitary feeders, although some groups can be seen at the surface, especially in association with areas of upwellings that drive the prey close to the surface.

Some Alcids such as the Little Auk or Dovekie and the Least Auklet carry the food to the chicks in their distensible gular pouch, whereas the Common Murre and the Thick-billed Murre carry a single fish in the bill.

But Razorbill and puffins are more spectacular while carrying several small fish crosswise in the bill, such as capelin, sandeels, herring or sprat, depending on the region.

The Cepphus guillemots take mainly small, benthic fish including sandeels, sculpins, rockfish, but also Zoarcidae, Pholidae and Stichaeidae. Usually, one fish at time is held crosswise in the bill.

The Great Auk mainly fed on benthic fish prey caught in deep waters by diving.

John Gould (1804-1881)

Great Auk eating a fish

The breeding season drives the auks to land for nesting. They usually prefer offshore rocky islands or headlands, in order to avoid predation. The breeding habitat of Cepphus guillemots requires rocky crevices or fissures in cliffs and boulder fields, but they also use abandoned burrows of other species and even artificial cavities in old structures.

The largest species such as the Razorbill, the Common Murre and the Thick-billed Murre, use mostly rocky cliff ledges, sometimes crevices or caves, or partially cover hollow.

Puffins and the Rhinoceros Auklet nest is self-excavated burrows in the ground of maritime slopes. Among the puffins, both Atlantic Puffin and Tufted Puffin favour grassy maritime slopes, whereas the Horned Puffin nests in rock crevices on sea cliffs or slopes. The Rhinoceros Auklet also uses the bare forest floor of densely forested islands.

Pair at burrow entrance

The small murrelets Synthliboramphus nest in cavities and hollows around tree roots or logs, and also in rock crevices, whereas Ancient Murrelet and Japanese Murrelet excavate holes in soft ground.

The Little Auk or Dovekie and most of the small auklets often nest in sea-facing scree slopes and boulder fields, rock rubble along the coastal beaches, and steep cliffs (Dovekie).

Alcids are more vocal at night at the colonies, and generally mostly silent outside the breeding season. The vocal displays are often associated with the breeding behaviour or some threat displays during encounters with predators or neighbours. They are also used by adults to communicate with their chicks.

Cepphus guillemots and Aethia auklets give soft whistles, whereas murres and puffins produce loud, raucous growls and groans.

The vocalizations of Alcids can be classified in three categories. In warning or distress, they utter sharp, single notes. During pair formation and to communicate, both mates give trilling calls. And finally, the aggressive encounters are accompanied by various sounds including hoarse calls such as clucks, snarls, growls, and series of quivering and gurgling noises. Males are usually more vocal than females, as they have to advertise and defend the breeding site.

During the breeding season, calls are usually given at night both in flight above the colony and from the ground.

Vocal communication between adults and young is used mainly in dense colonies, when parents search for their chick, while the chick utters wailing distress cries. The distinctive calls can be identified at distance and allow to reunite separated family members. This type of communication is fairly common in high density colonies.

The nesting habitat of Alcids varies, but most species breed in colonies established on rocky islands and sea cliffs along the coasts. Some species such as the Cepphus guillemots, form very dense colonies, like the Little Auk or Dovekie. However, the Spectacled Guillemot nests in small groups and sometimes as solitary pairs. Both Kittlitz’s Murrelet and Marbled Murrelet are non-colonial nesters, and their nest-sites are considerable distances inland, up to 75 kilometres from the seacoast. The Kittlitz’s Murrelet nests on rocky mountain slopes, while the Marbled Murrelet nests high on branches in the upper canopy in coniferous forests. The Long-billed Murrelet builds a nest in tree on a pile of mossy branches, but only 5-7 metres above the ground.

The other species form small, scattered or large, single or mixed-species colonies almost always facing the sea or in close proximity.

Most of them return to their breeding grounds several weeks or months before the egg-laying, during which they strengthen the pair-bonds, occupy the breeding site, mate and prepare the site for the egg. They usually show high fidelity to colonies and breeding sites, and often return to the same colony in several following years.

They are usually monogamous with long-term pair-bonds. However, in high-density colonies, some extra-pair copulations are reported, especially in Common Murre and puffins. To prevent this behaviour, the male stays close to the female during its fertile period, and fights may occur between males.

The courtship displays are known for some species. The Atlantic Puffin performs the displays near the burrow entrance, and these displays enhance the bill pattern with head-flicking, sky-pointing and billing between mates.

Elaborate courtship displays can be performed by some small auklets prior to copulation with the male running around the female in a low-hunched posture while uttering a chattering sound. The Little Auk or Dovekie performs head-wagging and billing. Within colonies, this period is that of intense territorial defence and mating activity.

The egg-laying is closely related to food abundance, especially in cold water system, and may vary according to the range. Chick-rearing needs food availability, involving faster and healthier growing and earlier fledging.

The auks lay large eggs for their size. The shape is usually pyriform or ovoid with variable colours and markings. The auks that nest in trees or on the ground have cryptic-coloured eggs. The usual clutch is often one egg, except in Cepphus and Synthliboramphus that lay two eggs.

The incubation varies depending on the species, with 41-46 days in puffins, 32-39 days in auklets, 32-36 in large auks, 31-34 days in Synthliboramphus and 27-29 days in Alle, Cepphus and Brachyramphus species. Both adults share the incubation in stints of some hours to several days.

The chicks are usually semi-precocial and have thick down, but they are brooded during several days (2-10) by the adults.

In this group, we can find the Little Auk or Dovekie, Cepphus guillemots, auklets, Brachyramphus murrelets and puffins. The chicks are fed by both parents inside the burrow or generally at the nest-site during 27 to 55 days according to the species. They become independent when they fledge.

But in the other group, the chicks are precocial. This group includes the Synthliboramphus murrelets that are small, nocturnal species. They lay two eggs and the chicks are well developed at hatching, covered with thick down, and with large legs and feet. They remain 1-2 days in the nest but they are not fed. After two days, the adults take them and the family group goes to the sea. The young are guarded and fed by their parents until they are fully grown.

In the third group, murres and Razorbill are diurnal species and nest on exposed rocky sites where the chicks hatch and are fed during 15-23 days. The flightless, partially grown chicks leave the nesting sites with the male parent which cares them for 4-8 weeks.

The chicks spend considerable time exercising their wings by flapping them vigorously, inside the nest or outside near the entrance. When the young are ready to depart, most of them climb to higher points to help them to fly off into the air, or make short flights down the slopes to the cliff edge from which they take flight. They perform a spectacular “parachute” flight while descending from high cliffs of 200-300 metres high, followed by the parents that call continuously to maintain contact with their young, before to leave quickly the colony in family group.

The predation is high during this exodus that usually occurs in the evening, and the unattended chicks on the water or on the beach are vulnerable to gulls or foxes. Injured or dead chicks are taken by predators on the ground. Numerous chicks are injured when they hit the rocks, or die from the impact, but good numbers survive.

At this period, the vocal communication between adults and young is all important but critical when thousands or more bird are involved.

The Alcids are threatened by introduced mammalian predators on their breeding islands, and by natural predators. Population declines are due to the negative influences of humans through direct exploitation, disturbance and destruction of the habitat, hunting, commercial fisheries and kills in fishing nets, oil pollution and chemical poisoning. Climate change may involve reduction of prey and decrease of populations. Deforestation and logging destroy the nesting habitat of some tree-nesting species. These threats have resulted in the reduction of population and range of some species.

This Pigeon Guillemot is unable to fly but it can swim. Here, it is attacked by a gull, but it will fight in spite of its injuries.

Western Gull immature and Pigeon Guillemot

Several species are evaluated as Least Concern, but they suffer from the usual previous threats. However, they often have large populations and currently, they are not globally threatened.

The Long-billed Murrelet, the Kittlitz’s Murrelet, the Razorbill and the Cassin’s Auklet are classified as Near Threatened, due to deforestation for the species nesting in trees, climate change that involves reduction of prey availability, and disturbance, pollution and predation.

The Craveri’s Murrelet, the Scripps’s Murrelet, the Japanese Murrelet and the Atlantic Puffin are listed as Vulnerable for the same reasons, and some of them have small populations.

The Guadalupe Murrelet and the Marbled Murrelet are listed as Endangered. The major threat comes from the introduced predators on the breeding islands. But logging involves the loss of the nesting habitat.

In the past, Alcids have been hunted by humans for food, feathers and oil. This is the main cause of the extinction of the Great Auk. Today, Alcids are still threatened by humans but in different ways.

The global protection of these birds is mainly at ecosystem level, with the protection of both breeding sites and nearby waters, but also public education and suitable legislation.